Is heavy meat consumption about choice? Is it about rights? Read on, and share your own thoughts below.

This post is the latest in a series suggesting that we'll only develop food systems that are ecological, healthy, just, and morally defensible when we face the challenges of industrial animal agriculture. Inspired by the ancient Stoic principle 'The Obstacle is the Way,' the series explores reasons that so many civil-society groups, governments, and activists deliberately avoid discussing the topic of meat. Begin the series here.

Rationale: “We can't tell people what to eat.”

I've heard it from climate organizations and food-justice advocates — that asking people to eat less meat is not acceptable. That it feels paternalistic. Annoying. Culturally disrespectful or even colonialist, [1] and maybe a violation of consumers' rights to eat whatever they want.

It's a delicate topic. The science shows that the industrialized world needs fewer livestock and less meat. Yet many civil-society activists and policymakers, even those focusing on food systems, steer clear. A few years ago a climate expert, on announcing his team's United Nations report showing significant emissions from livestock, felt the need to apologize that: "We don't want to tell people what to eat." [2]

Even as recently as 2024 a UN Food and Agriculture report on ending hunger within climate boundaries offered a list of recommendations that did not include reducing overall meat production or consumption. [3] Eight prominent scientists objected and criticized the report for obfuscating the clear need for cutbacks in global animal agriculture, for dismissing plant-based proteins, and for being vague about methodology. [4]

At the same time, advocates for climate, health, and equity call for big system shifts toward alternative energy or localization of agriculture. And they'll recommend that consumers make personal changes like using less plastic and taking the bus.

I've attended food-security conferences in North America and read a lot of food-justice reports, and I can tell you that livestock systems are rarely on the agenda for discussion. We'll hear reminders to eat more vegetables, and we'll hear about the advantages of regenerative agriculture, but rarely do we hear that we'll also need considerably fewer livestock animals and less meat or dairy. Activists and policymakers need to acknowledge the meaty elephant in the room.

Some of civil-society's reticence to talk about meat stems from appreciation of the realities of world citizens that depend on animals for their livelihoods, and of food-insecure people in our own communities. Food insecurity is tragic, and it offers no easy answers. But internationally, we'll need to recognize regional differences. [5] There's no need for Kenyan pastoralists or Inuit hunters to eat less meat. It's rich countries that need to reduce consumption of beef and pork by 85+% and poultry and dairy by 45+%, [6] especially urbanites who have plenty of plant-based options. Locally, we'll need to shift supports and subsidies away from animal agriculture and toward crops for human consumption. And we'll need to educate ourselves that simple plant-based meals are less expensive than meaty ones. [7]

Food advice is everywhere

"Eat keto." "Eat gluten-free." "Eat less salt." Don't eat sugar or carbs. Messages on what to eat are ubiquitous — some backed by expertise and some not so much. As well:

- Consumers regularly seek advice on what to eat (and not) — from professionals and podcasts, from diet and recipe books.

- For nutrition professionals, giving food advice is their job. Patients may or may not comply but at least get science-based information.

- Even the far-from-radical Canada Food Guide says we should get most of our protein from plants and eat less animal-based foods.

- Corporate agribusiness has no shame in aggressively telling us what to eat, with flashy ads for unhealthy, highly processed meats and snack foods. I don't hear consumers complaining that Big Food is violating their personal rights.

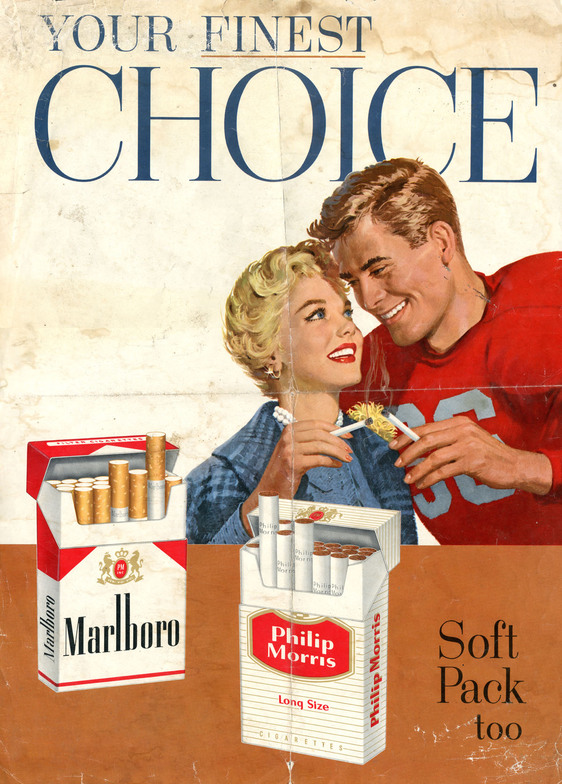

It's about balancing individual with community rights

We all support basic ideals of individual liberty, subject to limitations when choices harm others. When evidence mounted against cigarettes and second-hand smoke, tobacco companies framed smoking as a personal right. Today, most of us view that argument as bogus. But excessive meat and dairy consumption and production creates far more harm than smoking.

Big Meat factors into chronic diseases, [8] which lower quality of life and burden our healthcare systems. Mass production degrades ecosystems and adjacent communities. It undermines biodiversity and climate stability, by wrecking wetlands and rainforests to expand pasture and feedcrops. [9] It uses most of the planet's agricultural land and disproportionate amounts of fresh water. [10] And it creates conditions that fuel pandemics. [11] So it's pretty hard to argue that eaters have rights to consume whatever and as much as they want.

Our preferences are shaped by social and corporate messages

We're all born craving some saltiness, sweet, and fat to help us get enough calories and nutrients. But our specific food preferences are shaped by what’s available in our communities, what our families eat, and what's fashionable in our circles.

Preferences and food purchases are also heavily influenced by food corporations’ advertisements. [12] In Canada and the US, they’re mostly for animal products and convenient but highly processed snack foods. [13]

Maybe it’s aggressive marketing of certain foods that is interfering with our rights to a stable climate and healthy environments. This meaty marketing power is why I’ve argued in public-health forums that advertising of animal-based food should be limited, as is being done in regions of the Netherlands. [14]

Lobbyists are hard at work

Political pressure is an ingredient in organizations’ reluctance to say that the industrialized world needs less livestock and meat. For years the UN FAO has been lobbied by major meat-producing countries and agribusiness to be bullish on animal agriculture. [15] The FAO has a tough job, trying to reconcile human food needs with business objectives of its member countries.

We all have a tough job on this difficult file. Toddlers’ “don't tell me what to eat!” tantrums are playing out in the adult world, for food [16] and for over-consumption of all types, like flying, driving, and “retail therapy.” It’s holding back the shifts we need to stabilize our climate.

For us in civil society and the food movement, daring to speak more boldly could help remove this obstacle to sustainable and just food systems.

Images above: American ad for 'Choice' cigarettes, c. 1960s: Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising. Choice meat sign: Dyana Wing on Unsplash. Elephant image from kaffeebart on Unsplash.

REFERENCES

[1] See my previous Obstacle Is The Way series post on this https://www.eleanorboyle.com/blog/indigenous-people-eat-animals-so-we-cant-say-anything-bad-about-meat--99.

[2] Quirin Schiermeier, “Eat Less Meat: UN Climate-Change Report Calls for Change to Human Diet,” Nature 572, no. 7769 (August 2019): 291–92, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-02409-7.

[3] FAO, Achieving SDG2 without Breaching the 1.5°C Threshold: A Global Roadmap – Part 1, In Brief (2023), https://www.fao.org/interactive/sdg2-roadmap/assets/3d-models/inbrief-roadmap.pdf.

[4] Damian Carrington, “‘Bewildering’ to Omit Meat-Eating Reduction from UN Climate Plan,” The Guardian , March 18, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/mar/18/bewildering-to-omit-meat-eating-reduction-from-un-climate-plan.

[5] Chaohui Li et al., “Livestock Sector Can Threaten Planetary Boundaries without Regionally Differentiated Strategies,” Journal of Environmental Management 370 (2024): 122444, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122444.

Martin C. Parlasca and Matin Qaim, “Meat Consumption and Sustainability,” Annual Review of Resource Economics 14 (2022): 17–41, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-032340.

[6] See note [5] above.

[7] “Sustainable Eating Is Cheaper and Healthier – Oxford Study,” University of Oxford , 2021, https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2021-11-11-sustainable-eating-cheaper-and-healthier-oxford-study . Related Lancet article: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(21)00251-5/fulltext.

[8] Michael Klaper, Reversing Chronic Diseases with a Whole Plant-Based Diet , YouTube, 2024, https://youtu.be/lVfjdWLZHgs.

[9] Walter C. Willett et al., “Food in the Anthropocene,” The Lancet 393, no. 10170 (2019): 447–492, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4. See also: FAO, Livestock’s Long Shadow (2006), https://www.fao.org/3/a0701e/a0701e.pdf.

[10] Joseph Poore and Thomas Nemecek, “Reducing Food’s Environmental Impacts through Producers and Consumers,” Science 360, no. 6392 (2018): 987–92, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq0216.

[11] Michael Greger, Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching (Lantern Books, 2006); Eleanor Boyle, “We Need a Rethink of Big Poultry,” National Observer , April 29, 2024, https://www.nationalobserver.com/2024/04/29/opinion/beyond-biosecurity-alternative-solutions-bird-flu.

[12] Julia S. Guimarães et al., “Ultra‑Processed Food and Beverage Advertising,” Public Health Nutrition 23, no. 15 (2020): 2657–62, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020000518 . Open-access: https://udspace.udel.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/46e14cf7-4cf2-454f-b260-665524e53ebc/content.

[13] See Ellithorpe et al. (2022), cited above.

[14] “Netherlands Cities Show Leadership by Banning Ads,” https://www.eleanorboyle.com/blog/netherlands-cities-show-leadership--92.

[15] Arthur Neslen, “‘The Anti‑Livestock People Are a Pest’,” The Guardian , Oct. 20, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/oct/20/the-anti-livestock-people-are-a-pest-how-un-fao-played-down-role-of-farming-in-climate-change. Also: Cleo Verkuijl et al., “FAO’s 1.5 °C Roadmap for Food Systems Falls Short,” Nature Food 5, no. 4 (2024): 264–66, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-00950-x.

[16] Toby Park, “Don’t Tell Me What to Eat!,” Behavioural Insights Team blog, Oct. 16, 2019, https://www.bi.team/blogs/dont-tell-me-what-to-eat/.