Derek Glazer was a 12-year-old on holiday with his family at Dovercourt, in the East Anglia seaside town of Harwich, when the Nazi front first came terrifyingly close.

“Harwich was where you'd get the boat to Rotterdam [Holland],” explains Glazer. “And when Holland fell to Germany, we could very, very faintly hear the Stuka dive-bombers—and that was 50 miles away,” relates Derek. His father decided to delay the family's return to their London home and hunker down in Dovercourt indefinitely.

As defeat looked imminent, Derek's father declared: “If we're going to die, we're going to die as a family—at home."

But in the coming months, France was also taken. As defeat looked imminent, Derek's father declared: “If we're going to die, we're going to die as a family—at home.”

Living through London Blitz

In May 1940 Glazers returned to their home in the Hampstead Heath/Golders Green area of London, where their businesses included the stationery company David Samuel and Sons and a clothing-label company. They went on to live through a German bombing offensive that ultimately killed more than 40,000 civilians, almost half of them in London area, and damaged or levelled more than a million houses.

For more than five months during the Battle of Britain, Derek slept in a mattress in a corner of the living room—considered the safest part of his family home. He was one of many children whose classes were temporarily relocated outside of London.

Although his family was able to get him a private tutor instead, they were by no means spared the effects of what became known as the London Blitz. As they frequently sought refuge in bomb shelters, they learned how to distinguish the sounds of Germany's V1 flying bombs and its V2 ballistic missiles, which killed more than a hundred people in the Smithfield Market about six miles away from his home. Derek's father was one of two survivors (albeit with permanently impaired hearing) of the bombing that killed eight people in the small block of shops where his business was located. And there was the day in 1943, around noon, while Derek was out writing a pre-university French exam: the air-raid sirens wailed again, and a bomb shattered his street.

“I could see smoke coming from our home, so I said to my teacher: my French exam is on the desk—I'm going home,” says Derek. He blazed home by bicycle, at times having to carry it through “all the destruction”, and was relieved to find his mother and sister had averted an imploding kitchen window by huddling under a table.

“They were fine, thank goodness,” he says, wryly noting that his “typical English mother” seemed less concerned about the windows and their evasion of death than that Derek's lunch had been ruined. “I got back to school half an hour late for my 2 p.m. history exam, and just stared at the paper. Got 20%.”

Given the times, the fixation of Derek's mother on something so seemingly mundane – lunch – is understandable. By then, government rationing of meat, sugar, eggs, and fats like butter was in full swing. Britain's national “Dig For Victory” campaign was urging everyone to take up gardening to supplement their food rations, but the Glazers’ little patch was more likely to yield a few flowers and found bits of shrapnel than edible produce.

Sharing fairly

“Food was very tough.”

“Food was very tough,” recalls Derek, crediting his mother as a great cook who somehow made do while shunning the limited black market for controlled foods. As a growing teenager, Derek strove to share fairly: “I remember going into the larder... I was hungry, and took a tomato out to eat.” He got as far as the kitchen, thought of his young sister, and then put the tempting tomato back. “I wasn’t going to eat the family food!”

During World War II, imported delicacies like oranges were rarely seen in Britain and Derek “never met a banana”. But domestically grown apples, pears, and wild blackcurrants were abundant. To this day he treasures every bit of fruit that crosses his plate—even the parts closest to the peels.

As the war ended, Derek went on study commercial art, serve in the Air Force, emigrate to Canada, and develop a passion for growing flowers and vegetables.

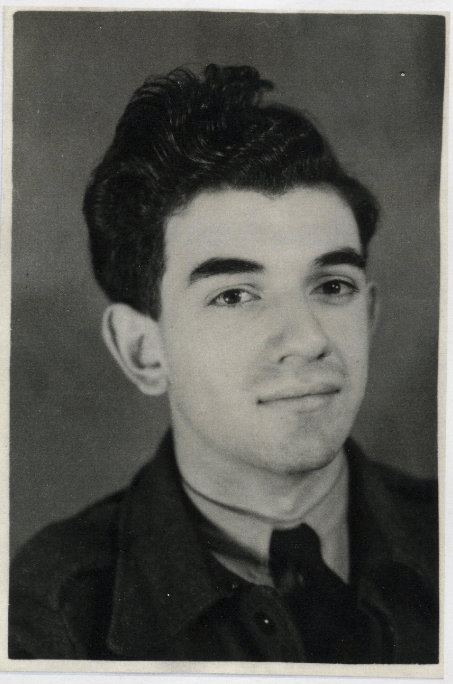

Derek in the Royal Air Force, age 20

“Everybody went through difficult times,” says Derek, who is now 91. He reflects that the English were nonetheless reasonably healthy during World War II, and points out that their hardships can't be compared with the atrocities of concentration camps. He's disturbed by widespread ignorance about this period.

“Too many young people don't know,” Derek adds. “I asked a young lad if he'd heard about Dieppe, and he said no... I couldn't take it. People just don't know.”