Could millions of people learn to grow their own vegetables, and change their diets to include more greens, less meat, and almost no sugar and junk food? It sounds like a nutritionist’s dream. But it happened in Britain during World War II when the country massively altered the diets of its almost 50 million citizens. Through a remarkable public education campaign, the country changed its food system and achieved more self-sufficiency, environmentally sustainable production, and better health for the population both rich and poor.

Britain’s wartime food transformation has inspired me to ask whether we could make it happen today. I’ve been intrigued by the potential of this for our time since my husband and I visited a fascinating museum exhibit in London called The Ministry of Food.[i] Here’s what we learned. When war broke out in September 1939, the British government had already designed a detailed plan for getting food to the millions. Painful memories lingered of WWI, when lack of planning had led to food shortages, high prices, and widespread hunger. This time, officials hoped to keep the population healthy on limited agricultural land and inputs, and with as few imported foodstuffs as possible. A densely-populated island, Britain had large food requirements. And the reality of war meant that boats might be bombed as they steamed toward the Thames with imported supplies.

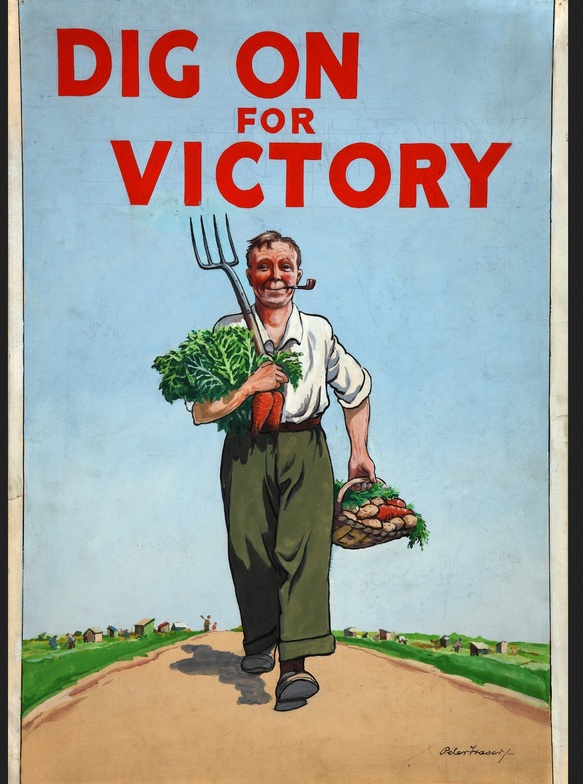

Within a week of declaration of war, government systems had been reorganized and a department created called the Ministry of Food. Under its auspices, the country began a multifaceted campaign for more local food production and new consumer habits. Every citizen was encouraged to ‘dig for victory’ by finding any piece of land that could be used to grow potatoes and cabbage. Based on research showing more people could be fed if land was used to grow vegetables and oats rather than meat, thousands of acres of grazing lands were plowed up to grow food directly for people. So much new land was cultivated, and so many men off fighting the war, that the Women’s Land Army was created and tens of thousands of young females recruited to work the fields.

Citizens were asked to make considerable changes in their daily lives – to accept rationing of meat, dairy products, tea, sugar, and cereals; to become farmers in backyards and allotments; and to create many ways to cook homegrown potatoes. Every Briton was persuaded to cut food waste by composting, by saving scraps for animals, and by using leftover vegetables and bones for soup stock.

In the tens of millions, people grew as much of their food as they could, and altered habits and recipes to minimize imports and rely mostly on locally-grown sustenance.

The campaign was breathtaking in its ability to elicit public support. Historical accounts suggest that most people welcomed the sacrifices, believing that the war was just and that the government needed to manage food supplies. While there was occasional grumbling, by and large citizens were willing allies with the Ministry of Food. For its part the Ministry showed leadership. Headed by a business executive who was seen as a compassionate and effective communicator, the Ministry rallied citizens through radio broadcasts and public meetings, explaining the reasons for the sacrifices and teaching people how to procure and prepare food in ways that would assist the war effort.

People needed to be taught the basics. How to dig. How to design a garden. How to compost. Don’t leave tools out in the rain. The Ministry conducted large-scale advertising to teach and to inspire enthusiasm for the campaign. My husband, Harley, is a historian and observed that the propaganda techniques used were ones that have been effective at other places and times. They elevated the campaign to a matter of national survival, and made individuals feel like heroes contributing vitally to the cause. Posters called for citizens to: Dig for plenty. Grow food in your garden or get an allotment. Help win the war on the kitchen front. Above all, avoid waste. Lend a hand on the land at a farming holiday camp. Eat greens for vitality. Better potluck with Churchill today than humble pie with Hitler tomorrow. Don’t waste food.

The results were dramatic. Production and consumption of vegetables and other local foods increased markedly. People ate more natural foods, and less that were processed. They got accustomed to brown bread rather than white. While few people were vegetarian, everyone ate frequent meatless meals. Wartime Britons ate modest but adequate amounts, and most were slim. The campaign had disallowed most culinary luxuries, but had ensured sufficient calories and nutrients. As a result, “the war left us healthier as a nation than we had ever been before or have been since,” says a recent publication The Ration Book Diet.

This volume, along with one called The Ministry of Food, suggest that wartime-style consumption would benefit us today.[ii] With our current food systems and habits causing problems for environment and health, it’s useful to ponder whether we could learn from the Ministry of Food. Could we implement sustainable food systems and rouse widespread commitment from citizens for the project? In Britain of 70 years past there was a war on, and one almost universally considered necessary given the terrible threat. As Harley commented, today’s enemy is environmental degradation, and it is largely a silent enemy. But we are at war for the health of the planet and survival of humanity, and so far it’s not clear we’ll win. Perhaps we can take some lessons from the Ministry of Food.

[i] The Ministry of Food. Exhibit on at the Imperial War Museum, London, England, running from February, 2010 to January 3, 2011. lwm.org.uk/food

[ii] Brown,M., Harris,C., Jackson,C. (2005) The Ration Book Diet. Gloucestershire: The History Press. Fearnley-Whittingstall,J. (2010) The Ministry of Food: Thrifty Wartime Ways to Feed Your Family Today. London: Hodder & Stoughton.